Parallel Skiing

Parallel skiing is where the skis stay parallel to each other all the time, no matter what you are doing. This is the goal for most skiers, as although having the skis parallel all the time can have many different implications, once you have got past the initial hurdles, skiing parallel will leave you with a more efficient, comforable, adaptable and enjoyable skiing technique.

Turns are obviously a large part of parallel skiing, and turns with the skis parallel are referred to as parallel turns.

Technique Changes

On this page we are going to look at some of the principles and consequences of basic parallel skiing, and what effect they have on technique. Starting off by considering one of the most basic variables, how far apart the skis should be.

How Far Apart Should The Skis Be?

This can vary a bit in more advanced skiing, but for basic parallel skiing there is a simple target, your skis should be and stay hip width apart. When your skis are hip width apart, both skis sit on the snow with the same edge angle, and your body is in its most natural and comfortable position. Yet this position still has all the movement you need in your body and legs available.

When the skis are too far apart, the downhill/leading edge on the uphill ski will dig into the snow, making the uphill ski unable to slide sideways.

Too Far Apart

When most skiers start learning to parallel turn they will often have their skis considerably further apart than hip width. This gives them a bit more static/low speed balance as they have a wider stance, but it does make turning a bit more difficult and slower because they have to move their body further sideways to move their weight from over one ski to over the other. This is a trade off between balance and ease of turning, and is not ideal, but it does not matter too much in the earlier learning stages. What is important, is not to have the skis too far apart, as this can cause problems. In parallel skiing both skis point and travel in the same direction, which means both skis need to sit on the snow in roughly the same way, with the same edge pushing into the snow (either both right edges or both left edges), to enable both skis to be able to slide in the same way and same directions.

When the skis are too far apart, the downhill/leading edge on the uphill ski will dig into the snow, making the uphill ski unable to slide sideways.

As the skis are brought further apart, the uphill ski will flatten its angle on the snow, and if the skis are brought too far apart, the leading edge on the uphill/inside ski will push into the snow. A ski can only slide sideways when the trailing edge is in the snow, with the snow hitting the underside of the ski. When the leading edge touches the snow, the snow pushes on the side of the leading edge, which makes the edge catch in the snow and stops the ski from sliding. This is a situation we want to avoid as one ski will get stuck in the snow, either tripping you up or sending you off balance.

In the snowplough we get away with having our legs wide apart, because we have the skis in a V-shape and only use the inside edges of the skis. This makes the snowplough stable because the skis are always travelling in a forwards direction, so that the snow always goes under the base of the skis before hitting the bottom of the trailing edges.

Too Close Together

At the same time as not wanting to have the skis too far apart, neither do we want the skis too close together. With the skis hip width apart there is plenty of movement available to lean the knees over and bring the skis onto their edges more. If the skis are too close together, the knees are not able to move as much, decreasing the amount of edge control that is available. Being able to put the skis on their edges more, is important for speed control, and vital for carving, a more advanced form of parallel skiing.

With the skis hip width apart, there is plenty of room to roll the knees over and lean the skis onto their edges.

With the skis too close together, it limits how much the knees can roll, so that the skis cannot be leant onto their edges as much.

Speed and Balance

When the skis are in a snowplough position you have a much larger static balance area.

A side effect of having the skis close together and pointing in the same direction, is how much your balance changes with speed. With your skis parallel and hip width apart, you have less balance at lower speeds than in the snowplough position, as you have to keep your weight within a smaller area. To have more balance you need to use the reactions from the skis to help you, but the skis won't react much unless you are going a bit faster. Just like riding a bike, if you go too slowly it is hard to balance, but as soon as you go a bit faster, small movements can have a larger effect, and make it much easier to keep your balance. Therefore it is best to attempt parallel turning when you are good and confident enough to ski at a medium pace, and are starting to feel you want to be leaning into the turns a bit.

When the skis are in a snowplough position you have a much larger static balance area.

Most skiers however, don't go instantly from stem turns with a large snowplough to parallel turns with their skis hip width apart. They generally make a slow transition into a parallel turn by making the snowplough used in stem turns smaller and smaller, until the skis end up parallel throughout the whole turn. This enables them to start by practising on flatter slopes at slower speeds, and build gradually towards steeper slopes at higher speeds.

The Edge Change

As having the skis parallel means that both skis are always pushing on the same edges, it also means there has to be a point where both skis swap the edges that they are pushing on at the same time. This is the edge change. This never happened in stem turns as the skis changed edges one at a time while initiating or taking away the snowplough.

When making a turn, the edges need to be changed at the point where the skis are travelling straight forwards, and not sliding to either side.

In basic parallel skiing we like to let the skis slide slightly sideways as often as we can, because it is good for keeping your balance and controlling your speed. For a ski to slide sideways the snow needs to go under the ski base before it hits the trailing edge, if the leading edge touches the snow it will dig in and stop the ski sliding (as explained here in edge effects). Because of this skis can only slide sideways in one direction at a time, which in turn means the edges can only be changed when the skis are not sliding sideways to either side. Therefore the edge change needs to be made at the point in the turn when the skis have stopped sliding sideways in their initial direction, and are travelling straight forwards. The edges need to have been swapped before the skis start sliding sideways in the other direction.

Although this sounds a bit daunting this is not something you need to worry about, as you will do this naturally at the correct time anyway, but the edge change is good to know about because it has implications for your balance, which is talked about in the next section.

Turn Phases

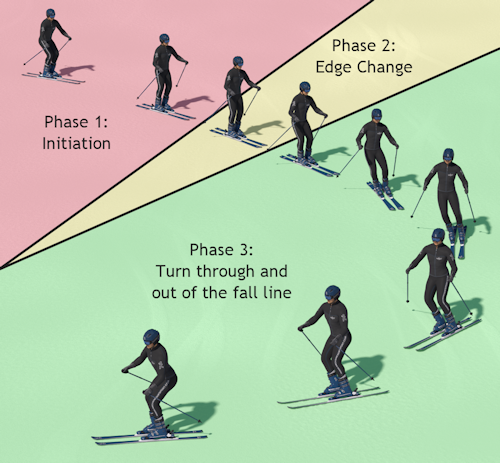

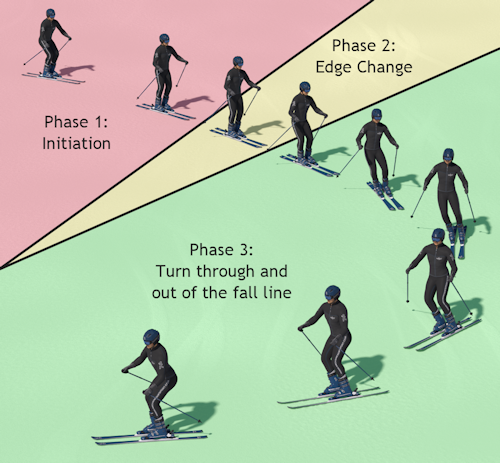

A parallel turn has 3 phases:

- The initiation

- The edge change

- Turning through and out of the fall line

The initiation is about turning the skis so that they are traveling straight, and decreasing the pressure on the edges, so that the edges can be changed. The edge change is about the actual swapping of which edges are being pushed into the snow. Turning through and out of the fall line is about finishing the turn off while controlling your speed.

One of the most noticeable differences between the phases is how your balance changes. In order to keep your balance laterally, you need to be able to push sideways on the skis, but you can only push sideways on the skis when the edges are pushing into the snow. The initiation is about taking pressure off of the edges so that the skis become flat on the snow, and about turning the skis to travel straight. Taking pressure off of the edges means you can't push on them much, and stopping the skis from sliding sideways means that there is also no movement to push against. So balance-wise the initiation is all about taking away your ability to balance laterally. Then for the edge change the skis are flat on the snow and travelling straight, making them unable to produce any lateral reactions to balance with, effectively making the edge change a balancing dead spot. It is only after the edge change when the new edges are engaged, that you can really start pushing sideways on the skis again, and regain good control of your balance. Because of this we generally want the initiation and edge change to be fairly quick, so that we don't spend too long being unable to do much to correct our balance. It's good to be aware of these reduced balance phases, as they never happened in the stem turn, and it is a feeling you will need to get used to.

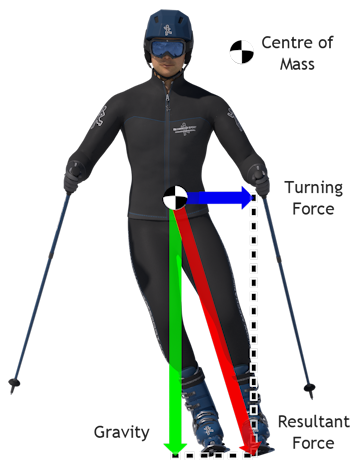

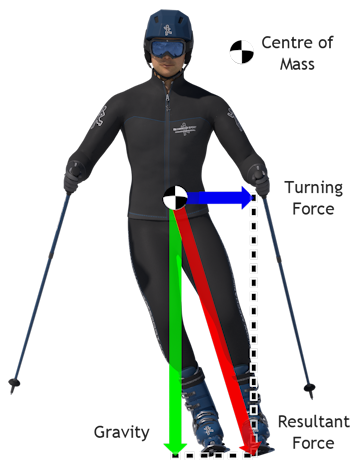

Leaning Over

As parallel turns are generally used at higher speeds than the stem turn, the forces that the skis produce while turning are also greater. Parallel skiing at higher speeds will be the first time that the turning forces have been large enough to lean over and noticeably bring our body away from over the skis. We still put our weight onto the outside ski as before, but now it gets transferred through the body at an angle. The diagram shows the forces when leaning over, with the resultant force being the overall force that you can feel. The amount we lean over will change depending on our speed, and how much the skis are pushing sideways on the snow. When leaning over in turns, we keep the upper body more upright than the legs for a more adaptable stance, that is good for edge pressure changes, and transfers our weight more efficiently.

Once you've started to lean into turns it's important to keep putting almost all your weight on the outside ski. If you have your weight spread between the skis, you will end up using the inside ski to support your weight, and the outside ski to push sideways with. This a bad situation as not only does it take away the dominance needed by the outside ski for good control, but with almost no weight on the outside ski it won't have much grip to push sideways with, making things far more difficult overall.

Upper Body Position

Your upper body plays an important part in balance, strength, stability, and precision in parallel skiing. However this is not done by throwing your upper body weight around, instead the upper body acts as the solid, stable foundation that parallel skiing is built upon. By keeping the upper body calm, you not only save energy from not throwing all that weight around, you have a stable base from which you can control other movements from. If you try to put a key into a keyhole while shaking your head and shoulders all over the place you will struggle to find the keyhole, because you have no good stable points to view or control your movement from. But with your head and shoulders steady, you can see and control what you are doing, and everything becomes much easier (as long as your weren't just at apres-ski). Your upper body works in the same way with your legs, with a stable upper body you can concentrate on where the legs are and should be, rather than trying to makes sense from limbs that are flailing all over the place.

Body Rotation

The position of upper body also makes a large difference to which muscles you use, and how much movement you have to control your balance with. By rotating the upper body so that the shoulders are turned slightly down the slope, you can push on the downhill leg using stronger muscles, while leaving more precise movement available for balance. You can feel this effect at home with a quick exercise.

These are not the only advantages to keeping the upper body pointing slightly down the slope however, because by turning the body like this, the body actually turns around less than the skis do. This saves energy from not needing to rotate the upper body weight around as much, and gives you a more calm and stable base to work from. Quite how much the upper body should be kept pointing down the slope though, is not as simple. It changes with how fast you are skiing, how much you let the skis slide, and how steep the slope is, which is covered in more detail on other pages. Basic parallel turns on a relatively easy slope as we are dealing with here, only require a small amount of rotation, just enough to put your weight on the outside/downhill ski, while having the advantages of using stronger muscles with better balance. What is important though, is that there is some rotation there, as it greatly improves balance, control, power and comfort.

Head, Arms and Poles

You should always look in the direction that you will be going in, this not only gives you the best view of the obstacles you might find, but it also help bring your body into the right positions. Your arms should be out to the side, not touching your body, with your hands in front of you, and the poles pointing back and out of the way. If you can't see your hands, you have let your hands come too far back. Your arms and hands should stay nice and steady, and should not move about much. Some of the mistakes people make with their head and arms can be found on the Common Mistakes page.

Turn Initiation Movement

A parallel turn starts with a very important movement, the initiation. It is important because it affects the whole turn, and any mistakes made here will cause you problems further into the turn. The initiation movement is simply moving your body upwards, forwards and slightly down the slope, while starting to transfer your weight onto both skis. As simple as this movement is, it is not a very natural movement, as your ski boots limit the movement you have in your ankles, and you have to move in a different way to how you naturally would. When you combine this unnatural movement with the fact some people can be hesitant to lean forwards and down the slope because they find it scary, things can become more difficult than they should be. Therefore, for most people this skiing specific movement needs to be learnt and practised.

The initiation movement can be split into 3 parts/components, each of which play an important role:

Extending Upwards and Across

Extending upwards and across comes from straightening your legs and moving your hips further over your downhill ski. It can be thought of as extending upwards at a right angle to the slope, rather than straight upwards. It can have several helpful effects, especially in more advanced turns, but in a basic turn the most important effect is that straightening your legs and bringing your hips further down the slope, takes away any knee roll and flattens the skis on the slope. This reduces the pressure on the ski edges which reduces the skis' resistance, enabling the skis to slide and turn around a lot more easily. This is important as without the upwards extension the skis can be very hard to turn around, making turns difficult to start, and take a lot longer.

Extending upwards takes pressure off of the ski edges, enabling the skis to slide and turn much more easily.

We don't want to straighten our legs completely, as we still need a little movement available to handle small bumps, and keep our balance with. Moving the hips down the slope is also an important part of the movement. The hips need to be brought down the slope over the downhill ski in order for the skis to flatten properly, otherwise the edges won't be able to be changed until the skis have turned into the fall line. If you are struggling with this movement, another way to think of it is to push on and extend the uphill leg, as this pushes everything in the right direction.

Leaning Forwards

Leaning forwards brings your centre of gravity, and pivot point further forwards, making the ski tips drop down the slope.

Leaning forwards makes the ski tips drop down the slope, turning the skis into the fall line. The forward lean comes partly from extending upwards and across, as straightening our knees brings our weight forwards, but we can add to this by leaning forwards with our upper body. Skis are designed to have their centre of resistance under the middle of your foot, so that if your weight is over the middle of your foot, the ski will slide sideways. When we lean forwards, our weight pushes further forwards on the skis, away from their centre of resistance. This creates a rotation force that pushes the ski tips down the slope, turning the skis into the fall line. Like anything though, the more we lean the bigger the effect is, and to create a force big enough for the skis to turn quickly down the slope, you need to lean forwards so that you are pushing on your feet just behind your toes. If the lean is not big enough, it will take a lot longer for the skis to turn, and if you don't lean forwards at all, the skis won't even begin to turn. Therefore leaning forwards enough, is an important part of making controlled turns, and reducing how long the turn initiation takes.

Transferring Weight

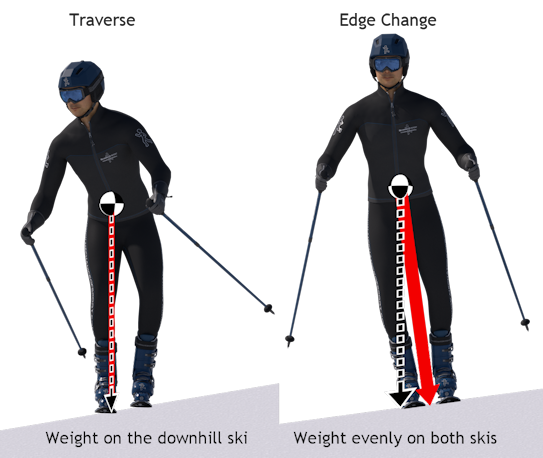

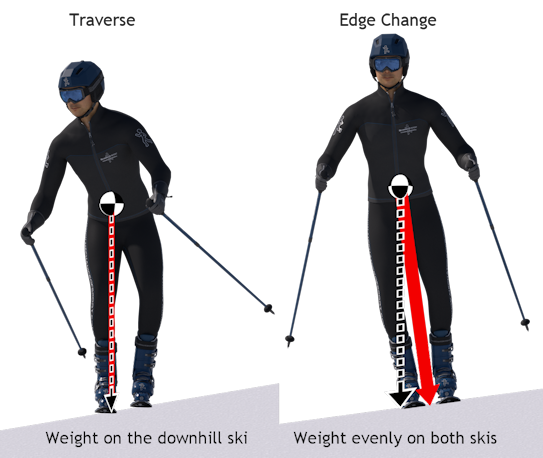

By the time you change the edges your weight should be split evenly between the skis, even though your centre of gravity has been brought further down the slope.

As soon as we start extending upwards and leaning forwards in the turn initiation, we also start to transfer our weight onto both skis. This gets you ready to start pushing on the outside ski a little further into the turn, and enables the weight transfer to be done smoothly. It also helps the outside ski to drop down the slope (lateral weight distribution). If you do not start moving your weight across onto both skis in the initiation, you will have to quickly apply pressure to the outside ski further into the turn, a bit like stamping down on that foot. Fast, sudden movements and pressure changes, produce fast and sudden reactions which are hard to regulate. We want our turns to be nice and round, and under control, which requires all movements and pressure changes to be made smoothly. Therefore starting to transfer our weight smoothly onto both skis in the initiation is another important part of making nice and controlled turns.

By the time you change the edges your weight should be split evenly between the skis, even though your centre of gravity has been brought further down the slope.

To complicate things slightly, transferring your weight onto both skis is not a movement, it's a change in muscle tension. You start to push down on your outside leg, enabling you to start taking pressure off of the inside leg. If you look at the diagram, the skier's centre of gravity is actually comes further down the slope than the downhill/inside ski, yet his weight is transferred onto both skis. This is a dynamic position, that requires some speed and movement to achieve, and is not a position that can be held for long, meaning that once a turn has been initiated properly, you will soon need to get on with the rest of it.

Next we will look at how to put all of these parallel skiing principles together in the Parallel Turns section.